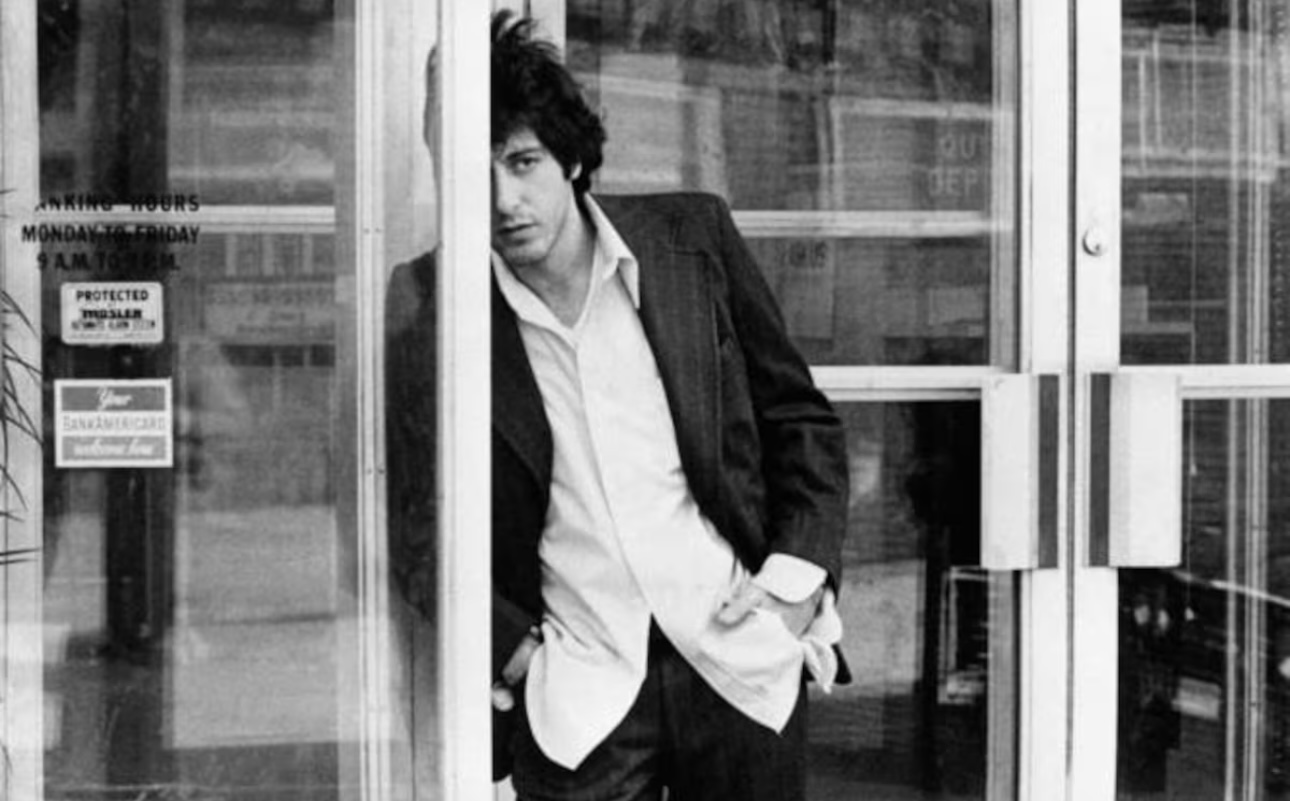

In October 2024, the world saw the release of a book everyone had been waiting for—the memoir of the incomparable Al Pacino, titled Sonny Boy: A Memoir. In 384 pages of candor and vivid memories, Al Pacino pulls back the curtain and allows a look into his private life. This article on bronx-trend.com takes a trip back in time to explore the legendary actor’s childhood, which he spent in the tumultuous and tough Bronx.

Family

Al Pacino grew up in the close-knit circle of his family. His mother, Rose, was just a young woman when she gave birth to him, in her early twenties, and his father, Salvatore, was only eighteen. Their marriage quickly fell apart, and the boy was left in his mother’s care. She worked tirelessly—at a factory by day and doing any odd jobs she could find in the evenings. But Rose always made time to take little Alfredo to the movies. There, in the darkness of the theater, she felt calmer, holding her only son close, whom she affectionately called “Sonny” after the song by Al Jolson.

Al’s childhood was marked by scarcity but also by the warmth of a large family. When his mother couldn’t manage on her own, they lived in her parents’ apartment in the South Bronx. His grandfather, Vincenzo, a native of Corleone, Sicily, was a strict and hardworking man. He had left school as a child, worked on coal trucks, and later became a plasterer. He was the true father figure for Al. His grandmother, Kate, with her blonde hair and blue eyes, had a completely different personality. She was a famous cook and the keeper of the home’s warmth. At the same time, she tried to protect her grandson from the prejudices of the era. When the boy would go outside with his face smeared with sauce, she would sternly wipe his chin:

“Wipe that off, people will think you’re Italian.”

It was a reminder of the distrust of Italians that still lingered after the war.

Life in their three-room apartment on Bryant Avenue was loud and crowded. Relatives returning from the war or simply passing through would often stay for a few days. Al slept either between his grandparents or on a sofa next to random guests. This chaos, full of voices and personalities, became the boy’s first school for observing people.

His family was Al Pacino’s first stage, and the people around him were his first characters, whom he learned to understand and embody. It was from this chaotic but warm world that his journey began.

Friends

Al Pacino grew up among friends who became his true second family. The courtyard of the apartment building in the South Bronx was always buzzing—that’s where Cliffy, Bruce, and Pete were waiting for him. Their crew was insatiable in its quest for adventure; every day seemed like a new journey filled with laughter, danger, and small discoveries.

Together, they raced through the streets, opened hydrants in the heat, clung to the back of buses, played pranks on older boys, and spent hours searching for coins through sewer grates. It was a friendship where everything was shared among the four of them: joys, troubles, and even punishments. And although each had their own story, together they felt invincible.

But this invincibility was an illusion. One time, his friends saved Pacino from a frozen river. Another time, Pete almost lost his hand because of a silly joke by Cliffy. Sometimes it seemed as if the streets themselves were testing the boys’ resilience. These adventures held a lot of danger, but also the wild energy of youth that felt endless.

Their gang was a motley crew, ranging from Bibby and Smokey to Johnny Rivera and Kenny Lipper, who would later become a Deputy Mayor of New York. But the most important ones for Al were still Cliffy, Bruce, and Pete—the ones who gave him a sense of belonging. They gave him nicknames: Sonny, Pacci, Pistachio. Among them, he wasn’t “Al Pacino,” but just a kid from the Bronx, one of their own. Sometimes they would appear outside his window and call for him to play, but his mother didn’t always allow it. Al would get angry, not understanding why he had to miss another adventure. It was only many years later that he realized: it was precisely because of her restrictions that he avoided the fate of his friends. Cliffy, Bruce, and Pete, who once seemed invincible, eventually died from drugs.

For Al, these losses were a painful reminder: he was saved not by chance, but by his mother’s vigilance and love, which protected him from that path. But the memories of his friends stayed with him forever—as a wild, vivid, dangerous, but priceless part of his childhood.

Baseball

Pacino had one special trait that set him apart from the rest of the gang: a love for sports, which his grandfather instilled in him. His grandpa was a devoted fan of baseball and boxing, and as a child, he rooted for the team that would later become the New York Yankees. In the lean years, he watched games through holes in the fence at Hilltop Park. The Yankees later got their own stadium, and his grandfather would sometimes take his grandson to baseball games, where they sat in the cheap upper seats. Al never considered himself underprivileged; the more expensive seats in the boxes were simply part of another world for him.

Pacino played on his neighborhood’s Police Athletic League baseball team. Sports didn’t interest Cliffy and the other boys in the gang, so he was essentially living two lives: one with his friends and one with his teammates. One day, returning from a game in a dangerous neighborhood, he was jumped by a group of young men with knives who demanded his glove. It was a glove his grandfather had given him. Pacino returned home in tears, wishing that Cliffy, Pete, and Bruce had been there. Their group was more than just a crew to him; it was a feeling of home and safety.

School and Theater

Al Pacino remembers that he was lucky to have people who believed in him even when he didn’t quite understand his own path. One of the first was his middle school teacher, Blanche Rothstein. She chose him to read excerpts from the Bible at a student assembly. The boy, who hadn’t grown up in a religious family, suddenly felt the power of the words that came from his mouth in a loud voice. This was the moment he first grasped the power of the stage.

School plays followed The Crucible, The King and I, A Good Murder. He would go on stage, sometimes as little Louie, sometimes as a boy detective, and each time he felt that the stage belonged to him. Pacino liked that people listened and watched, that he could hold an audience’s attention. But the real event was when, one night at the premiere of A Good Murder, both of his parents were in the audience. After the show, for the first time in a long time, they took him to a coffee shop together, where they talked calmly and even smiled at each other. For young Al, this was a real miracle—the feeling that the stage could bring people together.

One day, Al saw Chekhov’s The Seagull at the old Elsmere Theater in the Bronx. There were almost no spectators in the audience, but young Pacino and his friend Bruce were mesmerized. He didn’t fully understand the plot, but he felt the magic of the theater, and from then on, he carried Chekhov’s works with him.

With this passion, Al enrolled in the High School of Performing Arts in Manhattan. Every morning, he and Cliffy would take the subway from the Bronx, immersing themselves in the clamor of Times Square. One time, the friends even saw Paul Newman—a real star—simply walking down the street. This impressed Pacino more than any lesson: actors were real people, with real friends and concerns.

One day, Al met an actor he had seen in The Seagull at a coffee shop. The man worked as a waiter by day and performed on stage at night. This contrast made a huge impression on Pacino. He understood that acting wasn’t just about fame and glamour; it was also about hard work, a constant struggle for the opportunity to perform.

So his school, teachers, and first stages shaped him not just into a boy from the South Bronx, but into a future actor who learned to value the power of words, the magic of performance, and the people who pushed him toward his true calling.

His Mother

When Al was fifteen, life at home changed. His mother started dating an older man and even talked about possibly moving to Texas or Florida. For a teenager, this was a strange mix of relief and anxiety. On one hand, he felt his mother had a chance at new happiness; on the other, he didn’t understand if there was a place for him in that new life. But everything ended abruptly. The engagement was broken off by telegram, and his mother, shattered by the rejection, fell into a state of illness that doctors called anxiety neurosis.

She was prescribed treatment that they couldn’t afford, and soon Rose began to urge her son to drop out of school and get a job. Al didn’t object—school was not his world. Despite all his odd jobs, he remained hungry for the stage and for words. He cleaned studios to get a scholarship for classes, moved furniture with his actor friends, and at night, he rehearsed Shakespearean monologues on empty streets.

When the terrible news came—his mother had died of an overdose—the world seemed to stop for Pacino. He hadn’t had a chance to say goodbye, and the burden of guilt settled on his shoulders. Could he have saved her, gotten her treatment, been there for her? This pain stayed with him forever. In his book, Pacino wrote:

“If I’m lucky, if I get to heaven, maybe I can meet my mother there. All I want is the chance to walk up to her, look her in the eye, and just say, ‘Hey, Ma, did you see how I did?'”

The childhood and youth he spent on the tough but vibrant streets of the South Bronx hardened Al Pacino and made him who he is today. This is a story of survival, talent, a love for art and people, and incredible inner strength.