The South Bronx, as seen through the lens of director Daniel Petrie, isn’t just a neighborhood in New York—it’s an almost apocalyptic landscape. It could be compared to Hamburg or Dresden after the war, except the ruins were created not by bombs, but by years of decay, government neglect, and social catastrophe. In this article on bronx-trend.com, we’ll break down this film, shot primarily on real locations in the Bronx, which showed audiences a little-seen side of New York during a period when the borough was in a true crisis.

Pain, Despair, Disillusionment, and Exhaustion: The Film’s Main Themes

If you haven’t seen this movie, here are the main plotlines and characters. In the early 80s in the South Bronx, life was, to put it mildly, unattractive. The trash-strewn streets and derelict buildings belonged not to the police but to gangs, pimps, and drug dealers. In the heart of this chaos was the 41st police precinct, known as “Fort Apache.” For residents, it was a symbol of protection, but for officers, it was an outpost in hostile territory.

Serving there are Murphy (Paul Newman), a veteran with 18 years of experience, and his young partner, Corelli (Ken Wahl). They try to maintain order, even though their precinct is neglected and on the verge of closing. Added tension comes from the new captain, Connolly (Ed Asner), who arrives with the intention of strictly enforcing the rules but quickly faces the harsh reality of the Bronx.

A tragic turning point occurs when Charlotte (Pam Grier), a heroin-addicted prostitute, shoots and kills two young police officers. Her crime remains unsolved—until the dealer she tried to kill takes care of her himself. Her body is found amidst the garbage, a scene that becomes a symbol of the neighborhood’s hopelessness.

Murphy tries to find comfort in his relationship with a young nurse, Isabella (Rachel Ticotin). Their romance is brief and painful. He discovers she is addicted to heroin and later loses her forever when Isabella dies of an overdose.

Against the backdrop of his personal tragedy, Murphy and Corelli witness a horrific crime—two of their colleagues brutally beat a teenager, and one of them, in a fit of rage, throws the boy off a roof. Murphy feels helpless: will he have the courage to turn in his colleagues? His moral torment becomes the main tension of the film.

In the finale, Murphy decides to retire and tell the truth. But before he can, fate pulls him back to the street—he chases a mugger, and the film freezes at the moment of his leap. This is not only an open ending but also a symbol: the fight against chaos continues, even when it seems there are no more options.

Unexpected Box Office Success and Mixed Reviews

Fort Apache, The Bronx opened in the U.S., grossing $4.5 million in 795 theaters during its first weekend alone. In just 12 days, its box office reached over $11 million in 860 theaters. Overall, the film earned over $65 million worldwide—a significant success for a movie about the impoverished and crime-ridden South Bronx.

However, the critics were far from unanimous. On Rotten Tomatoes, the approval rating is 80% (based on 15 reviews, with an average score of 3.6/5). But the film’s contemporaries were less generous. Richard Schickelof Time called it “more like a TV movie,” noting that only Paul Newman lent the film any sophistication. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times wrote of “the most complete collection of cop movie clichés since John Wayne,” criticizing the excessive scenes and plotlines that went nowhere. Variety noted that while the film was strong in dialogue and acting, its plot was exceptionally weak. All of this shows that a commercially successful film doesn’t always stand up to critical scrutiny.

Initially, the film’s idea seemed promising: to show life in one of New York’s most dangerous neighborhoods, using the real-life experiences of police officers. It was meant to be a story about people trying to survive amidst ruins and state indifference. But in the process, the film lost its human dimension and turned into a collection of clichés from police procedurals.

Critics also pointed out that director Daniel Petrie had more talent for intimate dramas than for police thrillers. Despite the controversial reviews, Fort Apache, The Bronx has one undeniable value—it left behind rare cinematic footage of the South Bronx on the brink of two eras: the decay and decline of the 1970s and the gradual revitalization that began in the 1980s.

Protests During Filming

The arrival of a major Hollywood company in the Bronx was not seen by many local residents as a prestigious event but as an invasion.

“They were in our neighborhood, in our territory, and they were acting like invaders,” recalls Gerson Borrero, an activist from the Committee Against Fort Apache.

Activists obtained a copy of the script and were shocked that most of the Black and Puerto Rican characters in the film were portrayed as pimps, drug addicts, or criminals. They demanded changes and threatened lawsuits, organizing demonstrations.

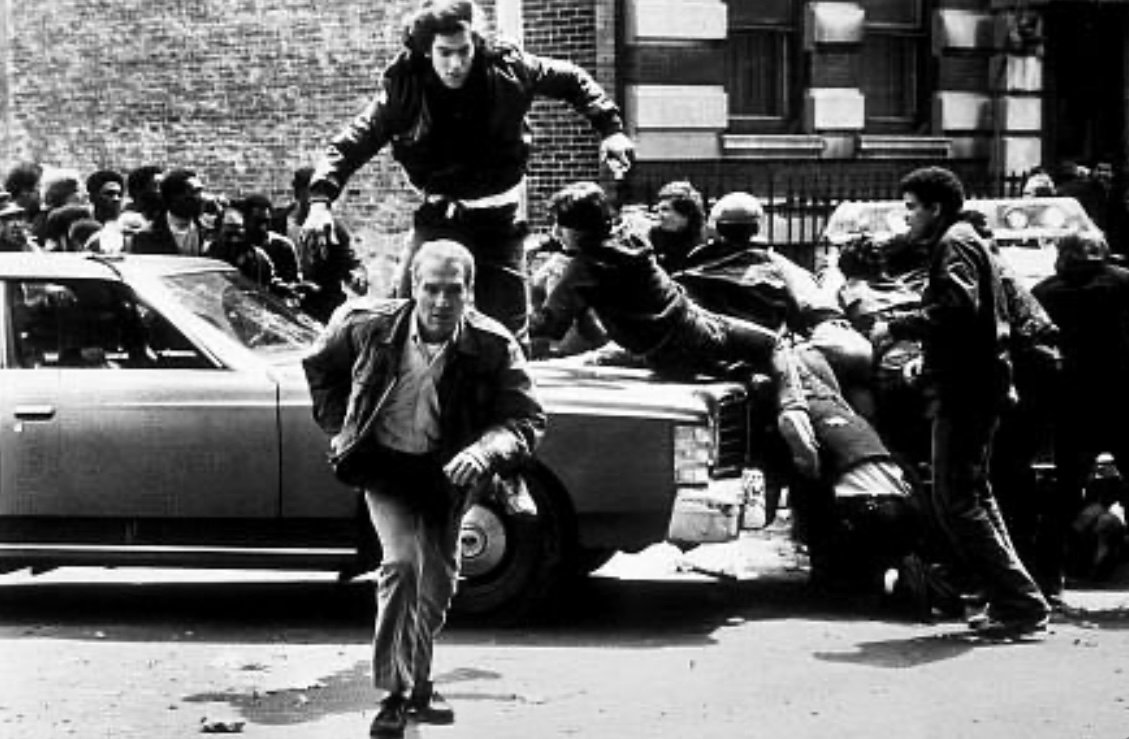

The situation quickly escalated. According to art director Christopher Novak, the film crew had to conceal filming locations to avoid protests. At times, it led to attacks: angry residents threw heavy objects, even smashed toilets, from rooftops onto the crew and their equipment. One such incident was incorporated into the film itself as a riot scene.

In interviews at the time, Paul Newman dismissed accusations of racism, emphasizing that the script was as critical of the police as it was of the criminals. Although no official changes were supposedly made to the script, Borrero believes the protesters managed to secure some concessions. As a result, a special disclaimer appeared at the beginning of the film:

“This story does not concern the law-abiding people of the Bronx and those who are working to make it a better place.”

Other Legal Disputes

Interestingly, as early as 1976, police officer Tom Walker, who had served in the 41st precinct, published a memoir titled Fort Apache, describing his experiences working in one of New York’s most challenging neighborhoods. After the film’s premiere, he filed a lawsuit against the filmmakers, claiming they had used his material without permission. Among the similarities he cited were identical opening scenes with the murder of two police officers, themes of cockfighting, prostitutes, alcohol, and the portrayal of Irish cops from Queens who frequently drank. Walker argued that these parallels proved plagiarism.

However, the court ruled otherwise. Both the federal and appellate courts found that it wasn’t a case of copying but rather the use of typical plot clichés that naturally arise in the police drama genre. Ultimately, the case was lost. The film was not found to have infringed on copyright.

Paul Newman himself also had a complaint, though not against the screenwriters but against the company Time-Life. The actor claimed that the television rights to the film had been sold to HBO at a low price—$1.5 million—when he should have received 15%. Furthermore, he accused the company of concealing over $3.75 million in foreign box office receipts, of which he was owed 12.5%. This conflict was resolved with an out-of-court settlement.

Preserving History

When the crew set out to film this movie in 1980, the Bronx still bore the scars of the tough 70s: neglected blocks, fires in abandoned buildings, and empty streets. Yet it was right here, amidst the real landscapes of the South Bronx, that history was being made.

One of the first recognizable locations was the Iglesia Cristiana Torrente de Cedron church on Louis Nine Boulevard. The camera captured its sign and the dark silhouette of the nearby elevated train station. The neighborhood has since changed beyond recognition, but in the film, it remains almost frozen in time.

The center of the entire story was the police precinct. Although the plot was based on the experiences of detectives from the notorious 41st precinct, the building of the 42nd precinct on Washington Avenue was chosen for filming.

Street scenes took viewers to the bustling commercial center of the Bronx—Third Avenue, known as the Hub. There, amidst neon signs and cheap shops, episodes were acted out that were meant to show the real rhythm of the neighborhood. And on the corner of East 164th Street and Boston Road, the dramatic moment with the man jumping from the roof was filmed. Remarkably, the building at this intersection has survived almost unchanged to this day.

One of the most powerful scenes was Paul Newman’s chase through Tremont Park. The camera captured the “Grand Stairway”—a majestic remnant of the former Bronx Borough Hall, which had been demolished back in 1969. The chase ended in another neighborhood—at the intersection of Arthur Avenue and 176th Street, in the heart of the Bronx’s “Little Italy.”

And the camera also captured the old Bronx Courthouse—a strange triangular building that served as the backdrop for a scene with a pregnant woman. The building disappeared long ago, and a college now stands in its place, but in the film, it remains forever.

Thus, in Fort Apache, The Bronx, one can see not only a fictional story about police officers but also a real map of the South Bronx in the early 1980s. These shots are a rare testament to how the borough balanced between the ruins of the past and the hopes for revitalization.